- The number of Americans in prison jumped over the past few decades amid the tough-on-crime policies of the “war on drugs” era.

- Current and former prisoners accounted for 5.8% of adult US men in 2010, up from 1.8% in 1980, according to data from Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

- High incarceration rates are likely to have contributed to the US’s decline in prime-age labor-force participation rates relative to other countries.

The United States is an outlier when it comes to putting people behind bars. It has the second-highest incarceration rate in the world, with the number of Americans in prison surging over the past few decades amid the tough-on-crime policies of the “war on drugs” era.

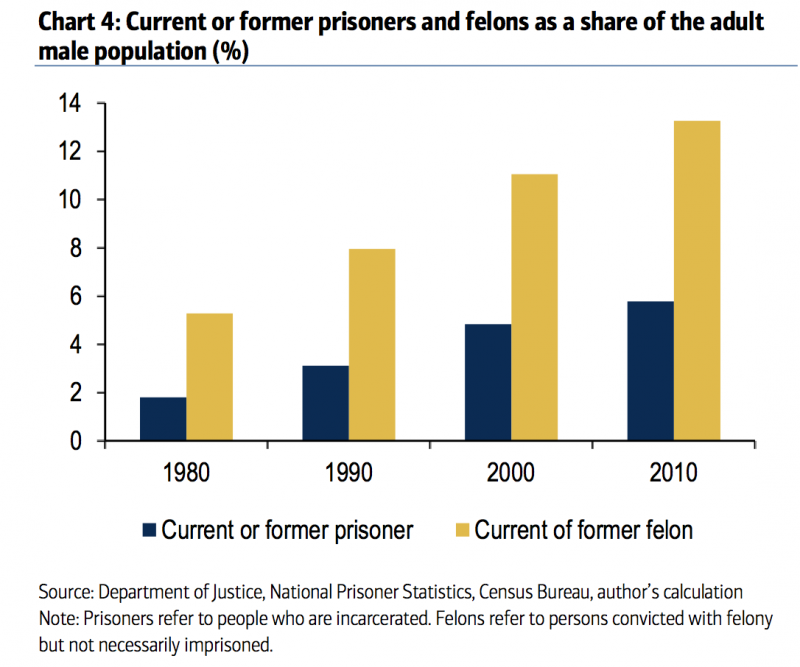

In a recent note to clients, Bank of America’s Michelle Meyer and Anna Zhou illustrated this with a chart showing current or former prisoners and felons as a share of the adult male population in the US from the 1980s into the 2010s.

The proportions have increased substantially over the past several decades. According to data cited by Meyer and Zhou, current and former prisoners accounted for 5.8% of US adult men in 2010, up from 1.8% in 1980.

“The growing number of incarcerations has left more people with criminal records, making it difficult for them to reenter the workplace,” they wrote. “Digging into the details by demographic cohort, we find that men make up nearly 93% of all prisoners, of which one third are between the ages of 25 and 34.”

Policies that produce a high incarceration rate have two key economic problems: They don't create alternative and better opportunities for those living in communities with high crime rates, and they don't address the question of how people should create new lives after their sentence.

And a high incarceration rate is likely to have contributed to the US's decline in prime-age labor-force participation rates relative to other countries.

"Incarceration policies affect participation rates directly by removing workers from the labor force for a period of time but also long-term as the stigma of incarceration can reduce demand for the labor services of the formerly incarcerated even years after their reentry into society," the Council of Economic Advisers under the Obama administration said last year in a report on the long-term decline in the US's prime-age male labor-force participation.

In fact, people who have been imprisoned are 30% less likely to find a job than their non-incarcerated counterparts, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, cited by Meyer and Zhou.

Occupational licensing rules or other restrictions on the hiring of those who have been incarcerated legally bar such people from numerous jobs, the CEA added. And even in cases with no legal restrictions, employers are less likely to hire someone with a criminal record. Several studies have shown that when companies receive two job applications that are identical except that one candidate has been in prison and the other hasn't, the formerly incarcerated candidate is less likely to get an interview.

A "potentially large fraction of this group is not participating in the workforce as a result of their incarceration, likely due to both discrimination and the degeneration of employment networks, resulting in long-term employment and earnings losses," the authors of the CEA report said.

"Those who emerge from the criminal justice system suffer stigma, hiring restrictions, and potentially reduced ability to work as a result, reducing the demand for their labor."